Very little is known about Romanian medieval literature. This is not a geographical statement, but a cultural one that focuses on language. While literature was most definitely produced within the confines of what would be considered Romania and therefore Romanian medieval literature does exist, literature of any kind was not written in the Romanian language until centuries after the medieval period.

A brief history should explain the different processions of the territory.

The earliest records of the Romanians indicate they initially inhabited the land of Dacia, modern day Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldova (the latter of which has been problematic until its recent independence). Around the mid third century the land was taken over by the Romans (which consequently brought Christianity to the people). Latin and Dacian mixed, and the dominant source of language, Latin, influenced the majority of the new language that eventually came to be known as Romanian. Interestingly, almost nothing is known of the Dacian language and its existence can be deciphered mainly by working backwards from early Romanian into Latin and noting the differences. In the mid sixth century Slavs invaded Romania, followed by several more invasions over the next six hundred years. Yet despite the disparate nationalities that were traipsing through the land, Romanians managed to maintain an almost impenetrable national identity and language, evident from historic accounts and linguistic studies which concur that while Romanian was influenced by its various invasions, the language only marginally acquired borrowed language, and to this day remains predominantly Latin based.

Nevertheless, the spoken language didn’t survive in extant manuscripts which mainly reflected the dominating nationalities, progressing from liturgical texts written in Latin, to psalters in Slavic, to general texts in Greek (while Romania was under Ottoman rule), until the early sixteenth century when Romanian as we know it finally became part of the textual tradition.

I rarely if ever encounter early texts written in Romanian, but today I was lucky and quite accidentally came upon a short poem written in 1644 by Udriste Nasturel, a scholar and poet. He was greatly concerned with the state of Romanian nationality in the face of so much diplomatic fluctuation where the country changed hands between neighboring nations on a consistent basis without ever holding autonomy.

His brief poem, “Stihuri in stema domniei Tarii Romanesti, neam casei basarabeasca” (Verses on the heraldry of the reign of the Romanian Country, nation of the House Basarab) already carries certain connotations in its title. Despite having been written in the mid seventeenth century, it recalls the rule of House Basarab that had solidified the Wallachia territory in the early fourteenth century, and successfully liberated the land from the Hungarians. Notably, while Nasturel is writing his work, the Romanian nation is juggling power back from the Ottoman Empire with various degrees of success. In other words, the title of his poem reminds his readers of their national descent from House Basarab, drawing on the houses’s success at fending off a vast enemy as a source of inspiration for a call to action against the Ottomans.

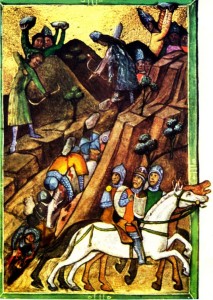

(The battle at Posada where the Hungarian forces were defeated by Basarab’s army – Chronicon Hungariae Pictum).

Secondly, “stema” has a double meaning of “heraldry” which I chose to use here, but also “tradition.” These are obviously intertwined even in our modern understanding as heraldry is steeped in tradition, but I think the latter word broadens the meaning outside of simply those who would use heraldry and becomes a nationally inclusive term. Tradition extends to an entire population of people who can identify with the symbols of their nation, as we will shortly see in the poem, whereas heraldry is far more confining to specific groups, namely families, and those in support of those families.

Here is the short poem with my own translation:

fericit acum se-au dat adaos peceţii.

Scut la pieptul corbului cu un semn ca acela,

om den jeţiu şezându-ş toiag laudă acela.

Mare neam băsărăbesc cu aceasta semnează,

că marea acelor isprăvi a toţ(i) să-i vază.

Happy now to have been added as another symbol.

Shield at the breast of the raven with a sign that he,

A man gripping his throne, praises it.

Large Basarab nation with this signs,

So their great feats all will see.

The poem has a very direct aabbcc rhyme scheme which serves to divide the narrative as each couplet depicts a brief episode of the story. Tellingly, Nasturel uses a Fourteener for his lines, a metrical line of 14 syllables which was commonly used between the Middle Ages through the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries for narrative poetry. Despite the brevity of his words, he is noting his larger intention.

This is a very image oriented poem that derives meaning from envisioning a connection to the past, not unlike the ways in which the title draws a connection between the contemporary audience and its ancestors.

“This” at the start of the poem does not refer to the Romanian nation, but another, namely the Hungarians, which would be understood by the image of the raven that sits in the middle of their national coat of arms. In the first two lines one possessing entity is subsumed by another, and by the end of the second line the raven is carried not by its original country, but added as a symbol – won over – by another nation. The seal of Hungary becomes a trophy for a victor in the battle, here referring directly to House Basarab.

The image of the raven is again brought to the forefront, depicted on the shields of men in battle, with its heraldic meaning directly related to the king. However, this king that praises the raven and its significance is here shown practically at the edge of his seat, gripping his throne as he is about to lose it.

The last two lines solidify the victory of the Basarab nation over the Hungarians. By overtaking the raven the Basarab nation “signs” its fate, and parades their victory in terms of the enemy’s flag for all to witness.

Further, the last two lines also draw another parallel between past and potential future victories. At the time Nasturel is writing this, the ruler of Wallachia, Matei Brancoveanu, who would soon help the Romanian people in pivotal fights against invaders, had recently declared his descent from House Basarab and consequently rechristened himself Matei Basarab.

And finally, by naming Basarab within the poem he also pays tribute to a man who just a decade earlier made it possible for men like Nasturel to practice their arts with greater efficiency. Starting with his reign in 1632 Matei Basarab was a great patron of the arts and scholarship. With invariable influence from his wife, Elena, who just happened to be Nasturel’s sister, Basarab became the founder of schools and a university, and was responsible for bringing the printing press into Wallachia. He was perhaps the most literate and literature oriented ruler the territory had at that point had, and culture flourished under his rule.

Thus in his brief poem Nasturel manages to navigate several narratives and tie together episodes from the past and present. What a neat little trick!

Sources:

Ghyka, Matila. A Documented Chronology of Romanian History.

Giurescu, Constantin C. The Making of the Romanian People and Language.

Johanna Granville. “Dej-a-Vu: Early Roots of Romania’s Independence.”

Teodor, Dan. Istoria Romaniei de la inceputuri pana in secolul al VIII-lea.

Theodorescu, Razvan. “Civilizatia romanilor intre medieval modern.”