In continuing my Arthurian research it has, perhaps most obviously, lead me to Glastonbury Abbey. While this is not necessarily conducive to my original goals, I think to better situate Paris, BnF, fr. MS 342 within the textual tradition, a broader survey of its various components must be taken into account. As MS 342 is a part of the Lancelot cycle that focuses on the latter parts, namely L’Agravain, Queste, and Mort Artu, it the last of these episodes that draws my attention to Glastonbury.

For those of you unfamiliar with the legend, most notably told by William of Malmesbury, to briefly retrace the history, in the seventh century Glastonbury Abbey had been built in the town of Somerset that had been previously conquered by the Saxons. In the tenth century it was reformed physically and conceptually by Dunstan (yes, *that* Dunstan). Then, the next change for the Abbey came with the Norman conquest of 1066 where the church was substantially enlarged with elaborate additions, a process that spanned the next several decades. By 1086, in the Domesday book it was stated to be the most wealthy monastery in the country.

(Stained glass of St. Dunstan- although this is not historic per se, and this particular image comes from a New York church circa 1920)

In the first century Joseph of Arimathea is said to have brought the Holy Grail containing the blood of Christ to a church, along with his body, where it was excavated in the twelfth century to produce relics of various natures in what was then known as Glastonbury Abbey. This is a fanciful account attributed to Robert de Boron, which would date the Abbey’s existence a good seven hundred years earlier. However, this legend is dubious for several more reasons, most prominently due to the fact that these findings along with other relics were found in 1191, following the fire at the abbey in 1184, drawing large crowds, and consequently funds for repair at the Abbey’s greatest time of need.

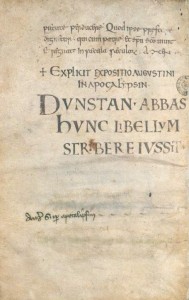

(MS Hatton 30 at the Bodleian Library with the inscription on the last page that the book was commissioned by Dunstan)

Medieval monks associated Glastonbury Abbey with Avalon, where not only the blood of Christ and his body were at one point thought to have been stored, but also the body of Arthur that supposedly constituted the aforementioned relics.

As for the the full history and minutia associated with the Abbey, refer to to William of Malmesbury’s On the Antiquity of Glastonbury, which actually prompted my research to diverge from its original intentions (if any could be said to have existed). I set out to find the history of Glastonbury in an attempt to assemble a tie between Arthurian legends and British history, curious as to why his legend had survived for so long on the cusp between history and fiction where historians and laymen alike desperately seemed to want his legend to be founded in fact. Surely it was due to the grandeur associated with Arthur’s court, even if not to Arthur himself, but anyone familiar with insular history will attest to the numerous real life dramas of the Middle Ages without a need to embellish further and create persons who never existed.

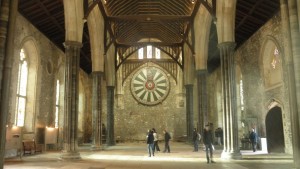

(Round Table in the Great Hall of Winchester Castle)

(Close up)

Yet Arthur weaves himself throughout various accounts, and his round table can even be found in Winchester Castle, prominently displayed on the wall of the Great Hall (see above). I began working my way through the different historiographic records, and recalled Arthur is not mentioned by Bede, but he is a prominent figure in Galfridian accounts, however these are polarized sources, so I referred back to William of Malmesbury, the catalyst for my inquiries. In doing so, I found something most strange – conflicting accounts by the same author.

This is where I am currently stumped. Unfortunately, it is the winter holiday break, leaving me with few people I can call upon for help.

The two differing accounts refer to William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum and De antiquitate Glastoniensis ecclesie. The former was composed circa 1125, while the latter came about in 1129, and therein lies the Arthurian question within a much larger historiographic problem.

In the Antiquitate, William of Malmesbury follows folkloric tradition of Arthur having been buried at Glastonbury Abbey with his remains serving as relics for medieval monks – a whimsical story for the masses, and certainly one that was quickly absorbed. However, I think it may be safely assumed that Arthur (at least as king) did not exist. William of Malmesbury’s retelling of the tale within his Antiquitate would make much more sense if it were an auxiliary work leading up to his magnum opus, Gesta Regum, where arbitrary localized legends were set aside in light of accuracy, especially considering his immediately apparent indebtedness to Bede. However, in Gesta, written later, he astutely asserts “Sed Arturis sepulchrum nusquam visitur, unde antiquita naeniarum adhuc eum venturm fabulatur,” meaning the place of Arthur’s sepulture was unknown, only to be undone by his later work, Antiquitate, where he affirms Arthur’s burial ground.

It appears he is regressing in his history, moving from a survey of British history to a myopic focus upon a single venue, complete with its history and tradition – one that includes Arthur. In fact, this is my only way of reconciling Gesta Regum with Antiquitate. I like to think they were intended for different audiences and thus catered to disparate tastes. However, this is my conjecture, and am basing this on only my reading of the works, hence my need, or perhaps want, for diverse opinions.

Essentially the question I am most stumped with is “why?” Why did a, for lack of a better term, “proper,” historian regress into popular history and pay homage to Arthur in a most factual sense as opposed to relegating him to folklore, or omitting his history altogether when discussing Glastonbury? While it would be easy to assume he may have been under the Arthurian spell that many others would be under for hundreds of years, his adamant denial of a tomb and final resting place for Arthur in prior works attests to his denouncement of fairytales. Yet he resumes his writing less than five years later to forge a dedicated place for the once and future king of Avalon, or Glastonbury. Why?