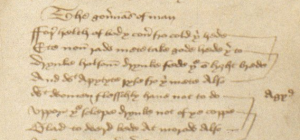

“For helth of body cover fro cold thi hede,” begins John Lydgate’s “Dietary,” within Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 61 (pictured above on folio 107r). The piece was extremely popular in various versions, and consequently survived within fifty-seven manuscripts, along with several early prints.

While the brevity of the work in Ashmole 61 is odd, the abridged version is not anomalous to the manuscript, and actually serves as an excellent survey of what might today be deemed homeopathic remedy in the Middle Ages since it cautions that “if so be that lechys do thee fayll,” and “if fysske lake, make this thy governans,” with the implication that there is an alternative to formal medicine and science that is found solely within the human body which is capable of self preservation.

According to Lydgate, the cure for all ailments can be achieved through “temperat dyet and temperate traveyle.” In other words, as the common idiom states much later, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” (which ironically Kaiser Permanente, a healthcare facilty, adapted), is at the heart of Lydgate’s prescription that boasts an independence from traditional healthcare.

The first stanza sets the tone for the entire piece:

For helth of body cover fro cold thi hede.

Ete non raw mete — take gode hede therto —

Drynke holsom drynke, fede thee on lyght brede,

And with apytyte ryse fro thi mete also.

With women agyd, flesschly have not to do.

Uppon thi sclepe drynke not of the coppe.

Glad towerd bede, at morow also,

And use thou never overlate to sope.

The first sentence is in line with common sense, denoting the piece will rely on rational instruction to guide its readers since the extremities of the body are first to feel cold, and covering one’s head can prevent chills, sniffles, headaches, and an entire line of maladies.

It proceeds in this vein to warn against raw meat that could potentially cause all sorts of illnesses, especially since sushi was not yet a delicacy in medieval times. Then the nuanced conduct manual delves into that which it promises via its title, dietary advice, prescribing moderation of food and drink. Interestingly, unlike other variances of this text, here the caution is towards “drynke” whereas elsewhere it states “wyne.” This is a difficult situation due to the context in which this piece is found; Rate, the self identified scribe of this manuscript, is obviously conservative by nature (a judgement I, and others, have made based on the other pieces he has chosen to include, and the ways in which he has altered the originals), making the exclusion of “wyne” seem inevitable despite other scribes and authors showing similar preferences. Either way, even when erasing the traces of alcohol from one’s diet, the concept of moderation and temperance remain, reminding the reader that temperance governs man, or at the very least, should.

The second stanza serves to solidify the premises of the first:

If so be that lechys do thee fayll,

Make this thi governans if that it may be:

Temperat dyet and temperate traveyle,

Not malas for non adversyté,

Meke in trubull, glad in poverté,

Riche with lytell, content with suffyciens,

Mery withouten grugyng to thy degré.

If fysyke lake, make this thy governans.

Clearly a fifteenth century audience needed didactic literature for everyday occurrences, or at the very least was interested in reading reminders on simple methods of conduct such as moderate eating, drinking, and the collection of seemingly frivolous earthly items “withouten grugyng to thy degré.”

The work continues in this vein:

To every tale to sone gyff thou no credens;

Be not to hasty, ne to sothanly vengeable,

To pore folke do thou no vyalens.

Curtas of langage, of fedyng meserable,

Of sondry metys not gredy at thy tabull,

In fedyng gentyll, prudent in dalyens,

Close of tunge, not defameabull;

To sey thy best sette ever thy plesans.

The desideratum for educational pieces was prevalent among Lydgate’s contemporaries, as evident by the numerous extant witnesses to such works such as “How the Good Wife Taught Her Daughter,” or “How the Wise Man Taught His Son,” both of which can be found within the same miscellany as “The Dietary.” In this light it only makes sense Lydgate would want to participate in the genre and produce a similar work that instructs its audience on proper conduct, if even if it is not of the variety primarily concerned with morals or social norms.

However, by the fourth and fifth stanzas it begins to digress specifically into those topics generally reserved for conduct manuals on morals and virtue:

Have in dyspyte mothys that be doubull;

Suffer at thy tabull no detrasion,

Not supportyng the werkys that be full of trubull,

All fals rouners and adulacion.

Within thy courte suffer no dyvysion

That within thy hous myght cause gret unes.

Of all welfare, prosperyté, and fuson,

With thy neyghbors lyve in rest and pes.

Be clenly clothyd after thyn astate;

Passe not thi bondys, kepe thi promys blyve.

With thre maner folke be thou not at bate:

Fyrst with thy better bewere for to stryve.

With thy suget and neyghbors to stryve it were scham;

Werefor I counsyll to pursew all thy lyve

To lyve in pese and gete thee a gode name,

And thus to lyve worschypfuly with man and wyve.

Note the conservative strain of the argument where the reader is instructed to adhere to rules of proper dress according to their own estate, perhaps directed towards those who overstep their bounds into a higher class structure than would seem permissible (recall the five tradesmen of the Canterbury Tales who take it upon themselves to behave outside of societally prescribed roles). Nevertheless, even within this edict there is a hint towards moderation where one does not use their station to broadcast too little or too much of themselves.

By the sixth stanza the work renegotiate’s its primary topic and returns to prescribing proper conduct solely concerned with one’s physical health:

Fyrst at morn and towerd bede at eve,

Ageyn mystys blastys and the aire of pestylens

Be tymly at messe — thou may the better cheve;

Fyrst at thy rysing to God do reverens.

Vysete the pore with intere dyligence,

Upon all nedy have compassyon,

And God schall send thee grace and influence

Thee to increse and thy possessyon.

Yet, while the apparent concerns of the stanza reside within the physical realm, there is an indisputable tie to imagery of the soul, and further to a spirituality reliant upon a division between the everlasting, the ephemeral, and the tangent, with an indication that the former would be victorious. Throughout the manuscript there is an abundance of orthodox piety preserved within each text, carefully chosen and placed next to others of its kin. The “Dietary” is placed right in between two such texts, “The Lament of Mary,” and “Maidstone’s Seven Penitential Psalms,” serving a dual purpose in its placement. The physical and earthly concerns of the piece offer a respite from the adjacent heavily devotional and emotional texts, while the moral interludes within the “Dietary” create a smooth transition and linking system to aid with the flow between the pieces. In other words, as the reader moves from the highly passionate lament, the dietary offers some breathing room before entering the psalms that are equally laden with vigorously dramatic language.

Thus, after Lydgate’s short interjection of moral conduct within this stanza there once again reemerges the themes associated with physical health:

Suffer no surfytys in thy hous at nyght;

Were of rere-sopers and of grete excese

And be wele ware of candyll lyght,

Of sleuth on morow and of idelnes,

The whych of all vyces is chefe, as I gesse.

And avoyd all lyghers and lechers,

And all unthryftys — exile this excesse —

And mainly dyse pleyers and hasardours.

But he cannot abstain from moral instruction, and with each turn towards the physical he encompasses a full spectrum of cautionary words ranging from eating too much too late at night to avoiding liars and lechers. At a glance this appears to be a very disorganized conduct piece that leapfrogs in between topics – a result of an author who cannot make up his mind as to which dimensions of daily life he wants to inform his readers about. However, it is this very information that is most useful for modern readers as it allows a glimpse into medieval lifestyles and consequently those things that were important to remember (in whatever order they are presented). More so, they echo sentiments with which we are quite familiar today and evince the similarities between our own understandings of healthy living and those found in the Middle Ages.

And off again Lydgate goes, in a flux between physical and spiritual activities:

After mete bewere: make not long slepe;

Hede, fete, and stomoke preserve from colde.

Be not pensyve, of thought take no kepe.

After thi rent mayntayn thi housolde.

Suffer in tyme, and in thi ryght be bolde;

Suere non othys no man to begyle.

In youth be lusty and sade when thou arte old,

For werldly joy lastys bot a whyle.

Drynke not at morow befor thyn apetyte;

Clere ayre and walkyng makys gode degestyon.

Betwyx mele drynke not for no delyte,

Bot thyrst or traveyll gyfe thee occasyon.

Oversalte metys doth grete oppresyon

To febull stomokys that can not refreyn,

For thyngys contrary to ther complexcion

Therof ther stomokys hath grete peyn.

The last stanza beautifully sums up our experience of reading the text thus far:

Thus in two thyngys stondys thi welthe

Of saule and of body, who lyst them serve:

Moderate fode gyffes to man hys helthe,

And all surfytys do fro hym remeve.

Charyté to thy saule it is full dewe.

Thys resate is of no potykary,

Of mayster Antony ne of master Hew;

To all deserent it is Dyatary.

EXPLICIT THE GOVERNANS OF MAN

Here Lydgate makes clear his conscious concerns with both body and soul as the “two thyngys stondys thi welthe,” overtly stating his intentions for the piece, and making clear the distinctions he set out to discuss – his discourse is not a wayward diatribe devoid of meaning and haphazardly fluctuating between various modes of moderation. He understands the connection between spirituality and good health and how the two are dependent upon each other. Much like one who is not in a good state of mind reflects his distress through physical ailment, so does one’s spiritual well being transmit to their demeanor and comport.

In short, man must diet, or restrain to moderation, both his body and soul, as those practices best govern man, or according to Lydgate and his audience, should.

Sources:

Ebin, Lois A. John Lydgate.

Getz, Faye. Medicine in the English Middle Ages.

Pearsall, Derek. John Lydgate.

Rawcliffe, Carol. Medicine and Society in Later Medieval England.

Schirmer, Walter Franz. John Lydgate: A Study in the Culture of the XVth Century.