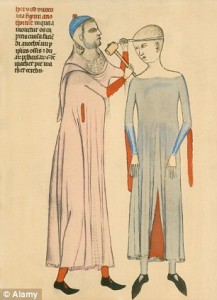

(Guido da Vigevano’s Anathomia Designata per Figures, 1345)

Earlier today I read Jenni Nuttall’s blog post about a medieval instance of a migraine in the context of a short poem. I was very intrigued so I started poking around on and off throughout the day until I came across another instance of a migraine in medieval writing that caught my attention, specifically in Harley MS 2390, a medical compilation of the fifteenth century (the manuscript begins in Latin and intermittently contains Middle English in various instances).

This particular manuscripts is an interesting patchwork of materials, with each apograph rooted in earlier texts dealing with cures for various ailments, and overall it is another compendium of the Speculum medicorum that has made its rounds from its inception in the twelfth century.

By folio 105 of Harley MS 2390 “3iff þere be any man or wymman þat / is dyshesyd in any dyuersse seknesses þat is for / to sayne …. Here is a man þat / is a conyng man in lechecrafft3 both yn ffy/sykke et surgere,” reads an advertisement for a physician who “wyl curyn ye mygreyn qwiche is a Malady3 yat takyth halff a man is hed & doth hym lesyn is sy3the of his yie.”

The word “migraine” comes into Middle English from Old French, via Latin, and was originally Greek, literally meaning having half a head, or skull. For anyone who has had a migraine, you will immediately recognize that that is an apt figurative definition since the process of having one very much feels like someone has smashed half of your skull, rendering you incapacitated for much else.

Much like in the poem Jenni analyzed, here too the ailment is characterized by a loss of sight, especially under the duress of light. However, what I found most interesting was the amount of detail used to describe a migraine (in both instances) which makes me question how well known the term was at the time, especially considering how few people today can accurately determine the difference between a really vile headache and an actual migraine. So perhaps the descriptors for the term served a double purpose of informing the public of specifically the type of ailment the doctor proposed to cure, but also as an emotive force to establish the potency of the doctor’s powers as he is able to overcome a condition that “takyth halff a man is hed and doth hym lesyn is sy3the of his yie.” And how does he do that you ask? Well, I don’t know since this advert promotes visiting the doctor to obtain a cure and does not actually deliver it in the text.

Afterall, as Chaucer’s Physician states best, for a doctor “gold in phisik is a cordial / Therefore he lovede gold in special.” So, pay him a visit, and a pound or two, and much like the Physician, the doctor in the advertisement can cure you of “everich maladye.”

(N.B. The picture for this post is from a medical book dedicated by Guido da Vigevano to Philip VI that included 24 plates. I chose the one here because it seemingly appeared to do with dispensing of head problems, and while this is correct it reaches far beyond headaches, or even migraines. This image illustrates the act of trepanation, or trephination, which literally meant to bore a hole, namely into the patient’s head in order to cure various ailments that would roughly translate into today’s version of the lobotomy, except that it occurred in a different part of the skull. I was very surprised to find that many people actually survived this procedure, although I don’t know to what ends)

Sources:

Bakay, L. “An Early History of Craniotomy.”

British Library, Harely MS 2390.

Voigts, Linda Ehrsam. “Fifteenth-Century English Banns Advertising the Services of an Itinerant Doctor.”