Today I had an amazing day at the Getty previewing their newest upcoming exhibition that will open just in time for the holidays on December 16, “Give and Ye Shall Receive: Gift Giving in the Middle Ages.” If you follow me on Twitter you may have noticed my mini flurry of tweets and pictures from the presentation, but here is a more in-depth look at some of the beautiful works you can see during the exhibit. I am personally super excited about going back and seeing the full array of manuscripts and pieces of manuscripts once they are officially on display. (Note: yes, the Getty knows I am posting all of these fabulous images).

The presentation was guided by Christine Sciacca, curator of manuscripts, and this exhibit specifically. She recently, as in a few days ago, went to retrieve some of the works that will be on display, and after brief introductions dove right in (because there is never enough time to really talk about manuscripts).

Gift giving in the Middle Ages functioned as a means of establishing connections, but the ubiquitous practice had far broader connotations than are immediately perceivable to a modern audience. Aside from obvious gift giving occasions, gifts were also considered a form of exchange and functioned within an economic medium. This latter definition further expanded the language of gift giving, and added nuanced understandings of how the objects operated – much of which has become ambiguous to us today. The idea of reciprocation comes to mind, and with it questions about the power relations involved, if any. However, before I turn this into a pseudo-anthropological discussion on the economy of gift exchange that perhaps strays too far from the intentions of this post, let’s return to the Getty exhibition.

A very popular gift during the medieval period was the book due to the arduous work that went into producing it (making it all the more valuable), but also the ease with which it could be customized and/or personalized. While looking at the several manuscripts and manuscript leaves today, a point I found most interesting was the disparity of the materials, from their various uses to the roles they played within the practice of gift giving. Sometimes these roles were obvious, as one book will shortly demonstrate, while at other times far more research needs to be conducted to discover how the manuscript fits into the gifting tradition.

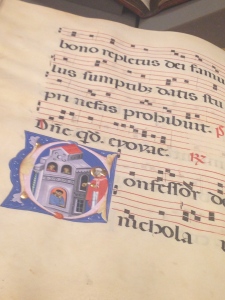

The first item we began with was a choir book from the late 13th century. As Christine reiterated during the presentation, medieval book size was often indicative of purpose, and a choir book, generally used by multiple people simultaneously, could get rather large. As each book has its own purpose, quirks, and identifying points, one of the most intriguing things about choir books (and antiphonaries) is their combination of music, text, and images, the latter of which serve as quick reference points for the different sections. While the period of this choir book occurred well before the heyday of similar works, which is generally considered the thirteenth century, it is an extremely beautiful and well detailed manuscript.

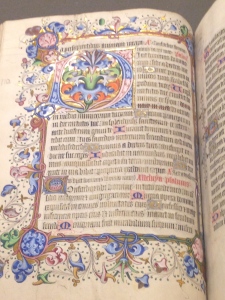

Here is a picture of the choir book in question that was most likely created in Bologna:

First, my poor picture taking skills will hopefully drive everyone to see the actual exhibit, because this obviously doesn’t do it justice. However, on this particular page the initial C that measures about my entire hand spread out, is illustrated with the image of St. Nicholas handing gold coins to a father who is in desperate need for a dowry for this two daughters (the tiny figures features in the top windows of the house) lest he be forced to send them into prostitution. Appropriately we viewed this manuscript on December 6th, the day of St. Nicholas. Even though this has nothing to do with the Getty, should you wish to read more about St. Nicholas, or view similar representations of him providing dowries to fathers, you can read about his tradition here, his connection to Sinterklaas here, and a Nation Geographic representation here.

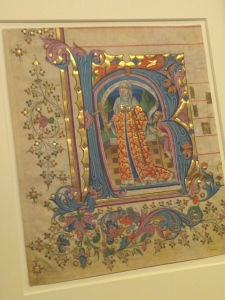

Choir books were often even larger than the desk sized one of the previous image as can be seen from the cut out here:

This is an initial K in a choir book from the mid fifteenth century from a cathedral in Seville, and the art tells us that is was worked on by the Master of the Cypresses (behind the female figure you can see his well known cypress trees). Among the many works attributed to this artist are over twenty mutilated choir books. Several of them are missing pages, and some have nothing but a few pages left even though the reasons for the various conditions of these manuscripts vary. Some were probably just lost over time, while some pages were taken out, or cut out, to accommodate newer versions of music. Such destructions of art appear unfathomable to us today, but at their time these manuscripts fulfilled necessary functions and changes were necessary.

The figure in the center is the female embodiment of Charity, or Caritas as she is here named in Latin. Her robes are extremely ornate in gold, with fur linings on her coat. Here she is the embodiment of her name, characteristically endowing those in need, like the beggar to her left, with a gold coin, while brandishing the cross in her right hand, very clearly linking Christ’s sacrifice to charity that must be passed forward among humans. Interestingly the cross is connected to a string that travels into Charity’s heart, and then the same string resurfaces and is affixed to the poor man to her left. While this depicts proper Christian conduct, and serves as a reminder of how we must behave to those who have less than us, I can’t help but also read it in a more cynical light where gift giving explicitly has strings attached, drawing attention to the duality inherent in gift exchanges.

The ornamented lower border, Christine mentioned, would be a running motif of this exhibition, as a reminder of the complexity of gift giving. It will be done in all gold, and should be quite the sight.

Before moving away from the choir books, to demonstrate the laborious process of using them on a regular basis, Christine showed us a picture from one of her recent trips that depicts a book stand for such incredibly large books.

This is an iphone photo I took of the photo she showed us on her tablet, so the glare and twice removed nature of it makes it difficult to see the details, but it is a very large contraption designed to hold multiple of these books, one on each of the ledge-like structures along each face, or flat surface.

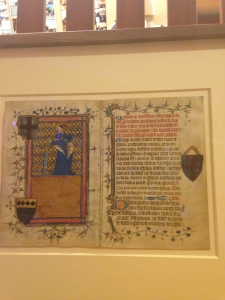

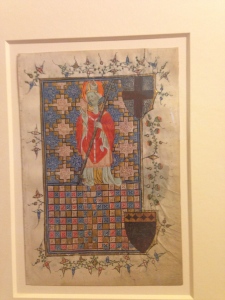

The next work we looked at was part of a larger collection, and on display were four leaves of a British Book of Hours from the late fourteenth century which have finally been brought together. Several more exist, but their whereabouts are currently unknown, and efforts are underway to locate them.

These come from different sources, such as the one on the bottom left of St. Nicholas reviving a youth that comes from the Berger Collection at the Denver Art Museum.

What typically stands out from these pages most, however, is the almost overbearing presence of heraldic representations. Heraldry is not my forte, but from what I gleaned from the conversation in the room, the language of heraldry acts as a barrier to deciphering it. Each color scheme (not even taking into account how colors in manuscript inks have often changed), each symbol, and so forth, exist within their own semantic world guided by elaborate rules. For a better understanding of heraldry, should you be curious, you can visit these notes on medieval English genealogy. In short, before decoding anyone’s coat of arms, the code of how these symbols were categorized must be learned, and from them can be found provenance, and even perhaps the reasoning behind a manuscript’s creation.

The numerous coats of arms that adorn almost every single page offer innumerable pieces of information about this manuscript, but for our purposes here, I will only focus on two things. It was likely created under patronage. While it probably acted as a gift, and as was mentioned during the talk, these symbols most feasibly broadcasted a union between families, it also hinted at the economic transaction built into the system of patronage. Even if the final gift was without expectations of reciprocation, the process undertaken to create this work extends into questions of not only what it cost to produce this manuscript, but also who was in the position of giving or receiving it. Even though the idea of gifts varying across the different socioeconomic classes is almost painfully obvious, here there is an even more stratified and nuanced distinction even between those occupying the same spaces in society. Of all the pieces looked at today I think this one appears to be (at least for me) the most puzzling, especially within its role as gift.

Thus I turn to the last piece we saw, Getty Museum, MS 17, where the reason for gift giving is significantly less problematic.

This is a charming fifteenth century English psalter. The author is unknown, and it could have been gifted numerous times from inception to its last known owner. However, it was within its last venue where another important facet of manuscript gift giving comes to the forefront: medieval manuscripts did not lose their luster, nor stop functioning as gifts at the end of the Middle Ages.

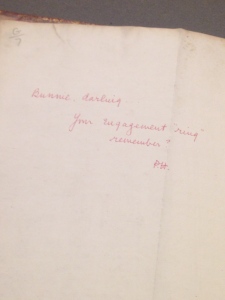

In the early twentieth century American book collector and bibliophile Philip Hoffer gave this medieval psalter to his wife, Frances. On the first page of the manuscript we find the inscription testifying to this:

Should you not be able to see the writing: “Bunnie, darling / Your engagement “ring” / remember? / P.H.” This book not only carried with it its monetary value, of which there was probably plenty, but the symbolic and sentimental value similar to what it once held.

I am sure I would have to conduct much more research into these works before forming any further conclusions, or even conjectures, but as these books changed hands during the act of gift giving they performed certain roles, and meant myriad things to their owners – givers and receivers.

Once again, I cannot wait to see the display in its entirety!

But, before ending the day, we were given one more generous treat by the Getty, and Anne Woollett, curator at the Getty, and specifically of the Spectacular Rubens: The Triumph of the Eucharist, gave us a guided tour of that exhibit. Photography was not here permitted since every piece is on loan from elsewhere, so I don’t have any lovely photographs to show you, but if you are in the Los Angeles area, it really is quite a sight that must be seen.

The exhibit focuses on a very specific aspect of Ruben’s work, namely the twenty tapestries with which he was commissioned by the Infanta, Isabella. The sixteen foot tall tapestries which were originally designed to tower over each other certainly challenge our notions of space. With only four in the room it appeared the images would permeate from their respective areas and into museum halls, so one could only imagine the full effect of twenty such works across vast walls and corridors. The exact placement of these tapestries has been disputed among scholars on various occasions, but the Getty does provide an example of a convincing way in which they could logically be placed with the confines of their original housing.

As I cannot here describe in words (and pictures would really not serve much better) the vivaciousness of the works, and since I have always been fascinated with the process of creation more than the end product, I will instead leave you with a recommendation of the book with the same name as the exhibit that is far better suited at describing these massive and amazing works.