Today I read this post on Medievalists.net debunking certain common myths about the Middle Ages (the one about tomatoes being poisonous was a new one for me), and it got me thinking about another common myth that I hear all the time: people in the Middle Ages didn’t love their children.

This reminded me of a paper I wrote a few years ago tracing the concept of childhood through time (however, for the purposes of the class I was in, it did not extend back beyond the 16th century). Out of curiosity I spent a little time today looking at different sources where children were mentioned in medieval writing to briefly outline the ways they were viewed (and I am purposely not looking at other representations via other forms of art, even though I am sure they would produce a bevy of marvelous sources).

I actually began by looking at Philippe Aries’ theory of childhood (since he pretty much started it all) and then Nicholas Orme who counters Aries’ argument almost to a point of literary attack. Orme (among others) believes Aries argued that children didn’t exist. Of course they existed. He simply postulated that it wasn’t until the mid seventeenth century that children, and by extension childhood, were seen as they are now. In other words, the idea that children are fragile, innocent beings in need of coddling and extreme protection is a modern convention. While he may have overstepped in his analysis when stating that children did not at one point in history receive love from their parents, he never outright stated this as can be seen from the very first page of his book, and his overall argument for the most part relied on the treatment of children and not the emotional implications of having them. I think this is the key to correcting the myth about parents’ lack of love for their children in the Middle Ages – it was not that they loved their children any less than they do now, but it was simply not exhibited in the same ways.

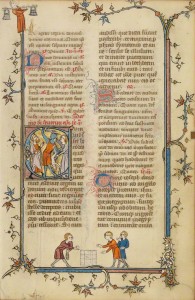

(A child is depicted in the Massacre of the Innocents in the middle, and at the bottom three boys are playing a board game. It is the bottom picture that is of interest – children taking part in what would appear to be normal childhood activities. MS Ludwig IX 2).

Children were sent off for apprenticeships or marriage at young ages, but for the most part, even if only through letters, they maintained contact with their parents who inquired frequently about their well being and at times even took action to rectify wrongs against their children. When conducting some unrelated research on the Yeoman in the Canterbury Tales I came across an article describing the relationship between the Yeoman and the Knight and Squire. Despite the title of the work (see below in Sources), the article is mainly concerned with the father/son relationship between the Knight and Squire, attesting to the unusual nature of a kin pairing at a time when most young men were sent off to fulfill their service under the tutelage of another. Basically children left the home at a very young age, and when they didn’t, their roles in the home would in modern times be regarded in a negative light, feeding the notion that children were either unimportant, unloved, and even abused. Yes, children would play (see above), their imaginations would get the best of them (considering the amount of medieval toys and infant instruments that we have catalogued), but they were also expected to fulfill certain roles that extended beyond keeping their rooms neat and picking up their things. No one had time for fantasy when there was water to be brought, bread to be made, wood to be cut, laundry to be beaten, and numerous other chores. However, delegating responsibilities earlier in the life of a child than is common today does not denote lack of love or emotional investment.

Another contributing factor to this myth is the shortage of children depicted in manuscripts. Aside from those of notable birth, few babies or small children can be seen gracing medieval manuscripts in illumination or text. A few have argued that this is due to the high infant mortality rates, meaning parents did not want to become attached to a child they could potentially lose. However, records indicate that many parents went to great lengths to save their children when possible, and R. Finucane shows evidence of parents going on pilgrimages to pray for their ill children or severely grieving their loss.

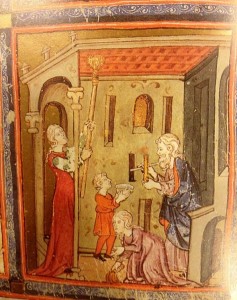

(Although this is the baby Jesus, and not a “common” child, the interesting part of this portrait is the baby walker being depicted. Not to mention this picture comes from an entire manuscript filled with domestic scenes that most of us would recognize today. Hours of Catherine.)

I also noticed a few pieces discussing the more natural order of infancy and motherhood, namely in regards to nursing a baby – a debate that continues well in our day. Le Chanson du Chevalier du Cygne et du Godefroid du Bouillon touches this subject in depth.

(Nature forging a baby. British Library, Harley 4425.)

(From the Golden Haggadah. A family portrait as everyone, including children, partakes in different chores).

This is a very brief discussion, but for more information (and a lot more manuscript pictures) go here, and/or see my direct sources. Enjoy!

Sources

Aries, Philippe. Centuries of Childhood.

Crawford, Sally. Childhood in Anglo-Saxon England.

deMause, Lloyd. The History of Childhood: the evolution of parent-child relationships as a factor in history.

Finucane, Ronald. The Rescue of the Innocents: Endangered Children in Medieval Miracles.

Hanawalt, Barbara. Growing Up in Medieval London: The Experience of Childhood in History.

Orme, Nicholas. Medieval Children.

Scala, Elizabeth. “Yeoman Services: Chaucer’s Knight, His Critics, and the Pleasure of Historicism”

Shahar, Shulamith. Childhood in the Middle Ages.