After researching the Crusades for the past couple of weeks for an upcoming conference, and after attempting to better acquaint myself with the material by running the gamut of historical narratives on the relevant events of the twelfth century, I realize very few of my findings thus far will make their way into my presentation since information on various battles and key figures is abundantly available and doesn’t require my detailed reiteration.

So, moving forward, since an axiomatic understanding of the success associated with the Crusades is at best biased, I am instead going to use Assassin’s Creed to guide my research (recall that the the topic is Medievlism in Pop Culture, specifically the video game Assassin’s Creed).

For those of you unfamiliar with the game, here is the basic information for it, from which I will focus on the original plot that takes place in the twelfth century during the Third Crusade. I am not entirely sure if this will be the best approach, but for my purposes here I am going to once again rely on some fact finding where I situate the main characters from Assassin’s Creed, the Assassins and the Knights Templar, into their appropriate milieux.

The Knight Templar figure should be, especially to a modern western audience, immediately recognizable. However, the chivalrous, noble knightly image we have all at some point ingrained in our head was not the only figure participating in the Crusades, and the period is marked by an onslaught of Franks from every social class, and even at times women, making their way towards the Holy Land to fight off non Christians. This was a time ripe with the ethos of fear which fueled secular ambitions for the Crusades that in turn provided the justification for violence and hostility, transforming them into a series of far less than pious endeavors. The etymology of the word “crusade” is in itself telling of how ideologies were manipulated to satisfy diverse goals. As early as when the Crusades started, the word did not exist. If language shapes our reality, or at the very least our perception of it, then the first knights deployed to the Holy Land were not embarking on anything more than a trek. The negative connotation associated with the Crusades was later fashioned once the atrocities became widespread. Even today, a crusade does not bear the implication of more than a mission or campaign, however, when stated in context of a proper noun, the Crusades take on the meaning they had developed over time, not of religious cleansing, but religious persecution.

Further, Augustinian philosophy was used to condone violent actions under very specific circumstances, especially when performing the work of God, and thus bridging the gap between the pacifism preached in Christian doctrine and the everyday terror in the Holy Land that had now become a natural occurrence.

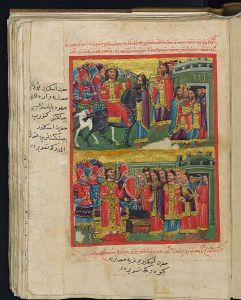

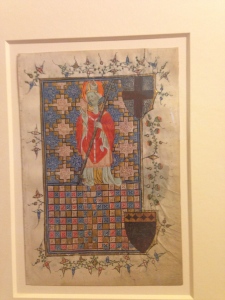

(Knights Templar burning at the stake, anonymous Chronicle, From the Creation of the World until 1384. Bibliotheque Municipale, Besancon, France)

By the thirteenth century the Knights Templar were no longer viewed as the heroes of Christendom, and as support for their various campaigns dwindled, they became persecuted not just in the Outremer and abroad, but also at home where they were systematically eradicated across Europe through arrest, dissolution of property, and eventual burning and hanging.

However, it was the methodology of their extinction that has cemented their existence and popularity into the modern day. Heresy charges against them were for the most part hearsay, and confessions were coerced through means of torture when the very institution which created them set out to annihilate the order as the church realized the Templars had grown to proportions beyond the control of a single body. The Templars, too, had realized their power once they began moving and acting as a single massive and autonomous entity. This, of course is an exceedingly simplified recap of events, and there was not any single factor that contributed to the Templars’ downfall. During the latter parts of their career they were at odds with numerous factions, amassing enemies at an alarming rate. Nevertheless, despite all of this, they were a considerable force, and to be so swiftly and cleanly wiped from society does not resonate very well with most sensibilities, hence the reemerging theories about their continued prosperity and secret existence, so well executed as to claim hold on our modern imagination.

Yet, this is what I believe it is – a fancy, a whimsy of fiction where history was dredged up and re-conceptualized for entertainment purposes. I have admittedly not conducted an extensive survey of scholarship dealing with this particular facet of Templar history, but among the works I have read I remain unconvinced of the historical accuracy behind the multiple popular culture reference to hidden societies descendant from the Templars themselves. But I am not here to necessarily articulate a tangible link, and the rehashing of history serves sufficiently for my purposes. I am not arguing that there is a line of descent from the Templars, or even that there could potentially be, but simply that interest in the subject, for various reasons has remained and can function as a conduit to the past in an almost allegoric sense where by reviewing history we can learn from it, which is exactly what I argue in my Assassins Creed paper.

As the collapse of the infrastructure that supported the Templars was occurring, the logistics behind this downfall remained obscured, and its various causes are still a mystery today. However, what I find most interesting is the use of the perceived Islamic threat that was used as a catalyst for the Crusades, and how that single connecting strand still stands. It would make little sense for Templars to continue existing in a vacuum. They were called into being for a reason and can only continue so under the same pretext, thus, for the Templars to exist, so must the enemy, whether real or perceived. This brings me to the Assassins, not just within the game I working with, but within historical accounts – rendering an even more complex image, to which I will return in the next section of this.

So far, even though my argument is not yet fully formed, I am having a lot of fun position the various pieces of information as I conduct more research, and I definitely look forward to untangling some of my findings on the Assassins.

If I don’t manage to post again in the next week, Happy Holidays everyone!

Sources:

Barber, Malcolm. The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple.

Barber, Malcolm. The Trial of the Templars.

Cowdrey, H. “Christianity and the morality of warfare.”

Haag, Michael. Templars: History and Myth: From Solomon’s Temple To The Freemasons.

Martin, Sean. The Knights Templar: The History & Myths of the Legendary Military Order.

Russell, Frederick. The Just War in the Middle Ages.