Castelloza has less than a handful of trobairitz songs attributed to her, just four actually, and only three are ascribed to her with irrevocable certainty. All of her songs are written in the canso form that was the most common among Troubadours and trobairitz alike. Very little is known from her vida except that she may have been from Auvergne and married to Turc de Mairona. Maybe. Distinguishing these facts from fiction seems like an almost insurmountable task at the moment, but it is also well outside my scope where I will share a piece of my current project, my translation of one of her songs, with a brief analysis. While the personal histories of the trobairitz were very interesting, their songs are the keys to a broader understanding of their culture, and perhaps even more importantly, a gateway to how their songs and society influenced poetry and the concepts of love for centuries to come.

Canso:

Amics, s’ie.us trobes avinen

humil e franc e de bona merce,

be.us amera, quand era m’en sove

q’us trob vas mi mal e fellon e tric,

e fauc chanssos per tal q’en fassa auzir

vostre bon pretz. dond eu non puosc sofrir

que no.us fassa lauzar a tota gen,

on plus mi faitz mal et adiramen.Iamais no.us tenrai per valen

ni.us amarai de bon cor e de fe

tro que veirai si ia.m valria re

si.us mostrava cor fellon ni enic;

non farai ia, car no vuoil puscatz dir

q’ieu anc vas vos agues cor de faillir,

c’auriatz pois caique razonamen

s’ieu fazia vas vos nuill falimen.Eu sai ben c’a mi esta gen,

si be.is dizon tuich que mout descove

que deompna prei a cavallier de se

ni que.l teigna totz temps tan lonc pressic,

mas cel q’o ditz non sap ges ben gauzir

q’ieu vuoill proar enans qe.m lais morir

qe’l preiar ai un gran revenimen

qan prec cellui don ai greu pessamen.

Assatz es fols qui m’en repren

de vos amar, pois tant gen mi cove,

e cel q’o ditz non sap cum s’es de me,

ni no.us vei ges aras si cum vos vic,

qan me dissetz que non agues cossir

que calc’ora poiria endevenir

que n’auria enqueras gauzimen,

de sol lo dich n’ai eu lo cor gauzen.

Tot’autre’amor teing a nien,

e sapchatz ben que mais iois no.m soste

mas lo vostre que m’alegra e.m reve

on mais en sent d’afan e de destric,

e.m cuig ades alegrar e gauzir

de vos, amics, q’ieu non puosc convenir,

ni ioi non ai, ni socors non aten

mas sol aitant qan n’aurai en dormen.

Oimais non sai qe.us mi presen,

que cercat ai et ab mal et ab be

vostre dur cor don lo mieus no.is recre,

e no.us o man q’ieu mezeussa.us o dic

qu’enoia me si no.m voletz gauzir

de calque ioi, e si.m laissatz morir

faretz pechat e serai n’en tormen

e seretz ne blasmatz vilanamen.

Friend, if I have found you being kind

humble and frank and with good mercy

I would love you so, yet when I recall

that I find you evil and cruel to me

I sing so that my song can be heard

of your good worth since I cannot suffer

that you are not lauded in every way

even as you continue bringing me cruelty and pain.Never shall I hold you valiant

nor fully love you with a good heart

until I negotiate the reality of it all

see if I show you an evil and cruel heart;

but I will not, because I don’t want you to say

that I have ever had a false and failing heart,

or to be able to say with reason

that in any acts I have failed you.I know this all suits me well in this way

even if everyone tells me this is not fitting

for a lady to plead with a knight as such

or to hold his time for so long,

but who says this knows not joy

that I would like to prove before I die

that in prayer I feel greatly renewed

to him who has given me heavy thoughts.

All are crazy who reproach me

for loving , as it is fitting to me,

and who says this does not know how it is

nor do I now look at you as I once did

when you told me not to be distressed

that at any time it will happen

that I will again have joy,

And these words alone fill my heart with joy.

All other love means nothing

certainly there are but no other joys

except yours that lifts and revives me

when I feel but only pain and distress

so I will be brought pleasure and joy

of you, friend, from whom I cannot convert,

I have no joy nor do I hope for help

but what rest I shall have when I sleep.

I no longer know how to present myself,

I have tried with good and with bad intent

your hard heart from which mine does not retract,

and this is no sent message, but I tell you myself

angered I will die if you do not want to give me joy

whatever manner of joy, and if you let me die

you sin and I will be tormented

and you will be villainously blamed.

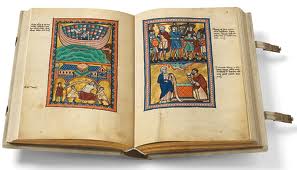

(Castelloza, BnF MS 843 f. 125 – the beginning of the poem cited above)

(Close-up of the same)

This highly stylized poem gives voice to her pain derived from unrequited love. In keeping with the courtly love tradition she first raises the beloved other upon a pedestal and gives him power over her while asserting his higher position in the world at large. However, in this assertion there is a certain double language in use – it is uncertain as to whether the lover was in fact of a higher class than her, but there is good reason to believe he was not, therefore if socially they were equals, her statement is false. Yet, even as equals, by virtue of being a woman she is below him socially, thus rendering her statement simultaneously true and drawing attention to the place of women in society as opposed to the artificial pedestal they sit upon in traditional Troubadour poems. Regardless of her title, class, or wealth, in love, much like in life, the woman is beneath the man and must beg his favor like Castelloza here does.

However, while begging his favor she usurps the male role in multiple ways. It is often thought that in the role reversal the trobairitz give a voice to the silent females of the Troubadour poems, but that is in fact not the case, and as I have argued before, these women find their own voices, separate from another. What I found the most interesting is that through Castelloza’s unrelenting praise of her beloved she manages to create a similar superficial pedestal for the male of her poetry where she uses words to elevate the man and synchronously place herself even higher, becoming a martyr to love. Petty and angry thoughts and gestures are beneath her, and she operates in accordance to a higher power. While she “non puosc sofrir” (cannot suffer) anyone thinking less of him, or for him to believe she “fazia vas vos nuill falimen” (has in any acts failed him), she unfailingly enumerates his various methods of mistreating her and casts the blame for her demise solely upon his shoulders, whose neglect is not only a fault, but a sin for which he must pay doubly – to God for having collaborated in her demise, and to the world who will blame him. Her love places him in a most precarious position, ultimately responsible for her well being, even if only to safeguard his own reputation. After all, his good name could not withstand women dying on the streets of Southern France from neglect.

Yet, what she wants from him is not simply attention, but “gauzir,” that roughly translates to joy, or “joi.” This concept emerges throughout the song, and carries several connotations, but there is one in particular I want to focus on – joi as related of joue (game) – and can lead to another form different from the canso that troubadours used, the jeu-parti. This reading of joi places her expectations into a different context and highlights the playfulness in her words. I don’t mean to detract in any way from the seriousness of her song because love at the time, along with everything it entailed, was indeed of crucial importance, but as she forces his hand in a response, she is essentially eliciting a game, while keeping in mind that games were not necessarily light matters either. Think of this type of game on par with chess or a similar cerebral activity that demands a certain level of involvement from the players while providing a comparable level of stimulation.

And it is this very stimulation that creates the extended metaphor for joi that can easily pour over into the meaning of a different kind of joy that also stems from stimulation, and then even further into joy which sustains itself simply through the act of loving.

Some have said Castelloza’s poetry is not as sophisticated or refined as the other trobairtiz, but her range of emotions combined with the various statements she makes demonstrate her prowess as a poetess and songstress, placing her on par with the likes of Comtessa de Dia.

While I am very much going to continue researching Castelloza and translating the rest of her songs, I do need to return for while to the Crusades and finish work on my conference paper that is quickly approaching. So, for those of you who have been enjoying my Crusades posts, there will be several coming in the next couple of weeks. As for my female writing fans, rest assured, I am not done.

Sources:

Bruckner, Matilda Tomaryn. “Fictions of the Female Voice: The Women Troubadours.”

Dronke, Peter. “The Provencal Trobairitz: Castelloza.”

Lazar, Moshe. “Fin’amor.”

Paden, William. The Voice of the Trobairitz: Perspectives on the Women Troubadours.