This post originally started with thoughts of summer and a search for manuscripts containing various poems or invocations for the season in an attempt to create a sort of montage. I found several focusing on songs, namely “Sumer Is Icumen In” from MS Harely 978, which got me on the path for searching out songs in general, when I came across the Chantilly Codex. I had previously read about it, but only in a cursory sense while looking for other things. Needless to say, my research for summer got derailed and I found myself looking over the Codex, and more importantly its significance.

The Chantilly Codex, Bibliotheque du chateau de Chantilly, MS 564, contains 99 chansons along with 13 Latin or French motets, many of which are examples of ars subtilior, a highly stylized musical form reliant upon complex rhythms and notations. While some consider this form as a branch of the ars nova directly preceding it, many others see it is as its own refined form.

The first thing that caught my attention is that the manuscript was not created all at one time, and not even over the lifetime of one person, but rather spanned several centuries with additions being made as late at the nineteenth century. Obviously this influences how the manuscript is regarded as it can no longer be seen as solely a product of the Middle Ages.

It is also worth noting that the first 12 folios of the manuscript are missing. I have little to say on this as I have been unable to find any explanation, but from what I have read it appears that the most likely scenario would suggest the folios were taken out before the book was bound since no damage to the book is reported. The implications here are many, but far more research needs to be conducted before any conclusions or even conjectures can be drawn.

Then the idea of authorship (a topic I am quite interested in) presented itself. Not only was the manuscript not completely written at any one point in time, but even when the majority of the manuscript was written it was not written in the traditional sense, but rather composed (pun intended?) by collecting materials from various writers. I am not sure of the exact methods of circulation, or even if the material was originally purposefully written. I have not found any articles stating whether the compiler sent word as to his intentions for his, for lack of a better term, anthology, or if he haphazardly came across various musical forms and decided to bring them together. The latter, however, seems unlikely in light of the techniques used throughout the chansons, pointing towards a more cohesive endeavor. Nevertheless, since the motif that started the manuscript can be traced all the way to the nineteenth century additions, the possibility cannot be dismissed that the original editor/scribe/compiler (without any evidence of there being a separation between these roles) didn’t collect as many pieces as necessary to find ones which he thought were the best fit. In other words, the pieces we have within the manuscript could have been a small portion of a much larger corpus that was sifted through to achieve the end product, and then the rest either discarded or lost.

Since there is so little evidence (just because I didn’t find any does not mean it doesn’t exist) of how the pieces were circulated, it would only make sense to question their origin versus the place where the manuscript was written (and here I am referring solely to the original pieces written in the fourteenth century and not the rest which would most likely have been added at different locations). This circles back to the authorship question, specifically the amount of people who took part in the compilation process. Was one person responsible for collecting the works, another responsible for sifting and editing, and a third responsible for the writing? Paleographic evidence from different sources (and most notably Virgina Newes) suggests several hands were responsible for editing the text even in its earliest stages since some parts are edited by a different hand using a darker ink. However, the majority of the main text was by all accounts written in one hand, probably English (which I think adds anther layer of complication to this French MS). As for the other questions, I have no answers, but am most interested in any studies that would provide some.

Another facet of this manuscript that is of interest is its actual construction. According to Lawrence Earp, French manuscripts of this period, when including musical pieces, always wrote the text before ruling the staves. For the Chantilly this is not the case, and the text came after as is evident from the multiple places where the black text overlaps the red lines of the staves (Elizabeth Upton). Also, ample space seems to have been left for decorative initial lettering. This is indicative of prior planning, and also of a unification of text and song – it was assumed that one would accompany the other, forming a cohesive unit. Further, the scribe allowed space for the melisma, another characteristic inherent within the music and thought to induce a chant-like hypnotic quality in the sound (think of choral music).

One of the last points I will touch on is that fact that the manuscript is not finished. While there is no evidence that more songs were to be included, there is obvious space for artwork that never was, despite the work being bound and written on rather expensive parchment. Numerous theories exist as to the reasoning behind this, ranging from conjunctures about the initial commission of the manuscript (that was probably for private use), to the whereabouts of the scribe and/or atelier working on the piece. I am more willing to believe that something happened to the commission rather than the scribe – another scribe or atelier could have been employed, especially since judging from the materials used and the evidence for the initial plan all indicate that whatever patron (if any – remember this is all still conjuncture) was paying a hefty sum for the piece.

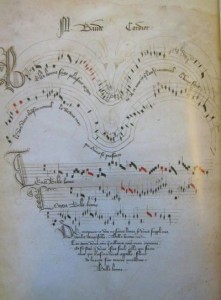

Nevertheless the manuscript was somehow reworked into circulation since it was bound, and then (possibly) later rebound, while several pieces were added to it throughout the centuries. In fact one such piece is ironically the one infamously associated with the manuscript above all others despite having only made its way into the binding in the late nineteenth century (pictured above).

There is a great deal more to learn about the Chantilly Codex as there appear to be a number of mysteries in regards to its origin and purpose, or raison d’etre, along with its movement through history. In the meantime, should anyone wish to hear what the music of the manuscript sounds like: